The technology sector is being transformed by AI and this is challenging many software vendors. Established players are working out the best ways to incorporate AI into their offerings while AI-native developers are disrupting sectors which have changed little for years. A key element in all this is pricing. Developing a pricing model that balances competitiveness with value delivery, and which aligns with business objectives is something many vendors, particularly startups, pay insufficient attention to. The result is often value being left on the table and a pricing model which fails to optimise returns for the vendor.

However, help is at hand with a new book by software pricing expert, James Wilton. Capturing Value provides a blueprint for vendors, new and established, to help them navigate these choppy waters. In this interview with James, he discusses some of the key messages from the book that is based on his extensive experience helping companies of all sizes develop optimized pricing models.

Martin: Could you start with giving an overview how you got into software pricing as your specialty?

James: Sure. After college I went straight into management consulting. First at AT Kearney and then internal consulting at Reed Elsevier, now RELX, before landing at McKinsey to lead the pricing service line for FUEL – McKinsey’s practice focused on fast-growth tech. I spent a number of happy and productive years there, working with start-ups and fast-growing tech companies and helping them develop pricing strategies. In 2021, I founded Monevate, a pricing and monetization firm for SaaS and tech companies.

Martin: Your career seems to have developed alongside the software industry move to SaaS and the resulting growth in different pricing models.

James: Absolutely, when I first started at RELX in 2012 you were seeing massive migration over from perpetual license type models to some form of subscription. I started off my career making those migrations happen. And then as usage pricing became more prevalent, I started considering a wider range of metrics to help companies make the transition and capture more value.

Martin: Are there some common mistakes you see with startups and their pricing strategies?

James: Interestingly, I think many companies are still struggling with the same issues they did 12 years ago when I started working with software companies. A common problem is that many startups don’t think of pricing as a strategic lever when they are building products. They tend to see it as a tactical decision which needs to be made and generally copy what the competition is doing. One of the things I continually bang my drum about and discuss in the book is that you need to devise a pricing strategy in line with your business objectives.

Startups often set their list prices too low. As a company grows, it becomes harder to increase your pricing strategy as customers become anchored to particular price points. Startups should solve this by setting their list prices high, and discounting when the product is an MVP. In this way they can lay out what their plans for the product are, how value will increase over time and how that will change pricing. But at the moment, while this is an MVP, there is a discount.

Martin: How should companies use their competitors’ pricing models when formulating their own?

James: Your pricing model certainly shouldn’t be dictated by your competitors’ models. Their models are based on their objectives, and they probably aren’t the same as yours. It is important to know what they are charging but you shouldn’t just try and match them. You need to look at what value they are providing at those levels and adjust yours from there. So, if you think your product is much better than your competitors’ then don’t price at the same level as they will likely respond and lower their prices.

You should be saying, “we are 20% better than these guys and, therefore, out price is x percent higher.”

Martin: So how can you demonstrate that you are 20% better than your competitors?

James: Well, this will vary from product to product but at a minimum you need to understand why your customers are buying your product. How does your product create value for them? Are you helping them grow their revenue or increase their efficiencies by doing x, y or z?

Whatever the sources of value are, how does your product enhance that? If you can draw a line between your product’s capabilities and those of your competitors, then you have something you can easily sell. In a lot of cases, you can do that in more of a qualitative way to explain how you are better in specific areas.

I’ve seen many situations where companies can directly quantify what the impact of their product is. They have data to show much they can save customers on costs and demonstrate the value being delivered. This can help when you are charging more than competitors and a quantifiable measure of value can justify that.

Martin: What are some of the mechanisms companies can use to demonstrate this value?

James: This will depend on the complexity of the product and the sale. Sometimes this requires salespeople to talk customers through the issues or an online value calculator may be useful. Very often, just explaining clearly on your website how your product adds value in specific scenarios is sufficient. The PowerPoint plugin, think-cell is a good example of this. I’ve been using it for about 15 years to help me create charts on slides and the company does a great job of explaining the time their product saves users in this process. For a management consultant, this timesaving is a key value proposition.

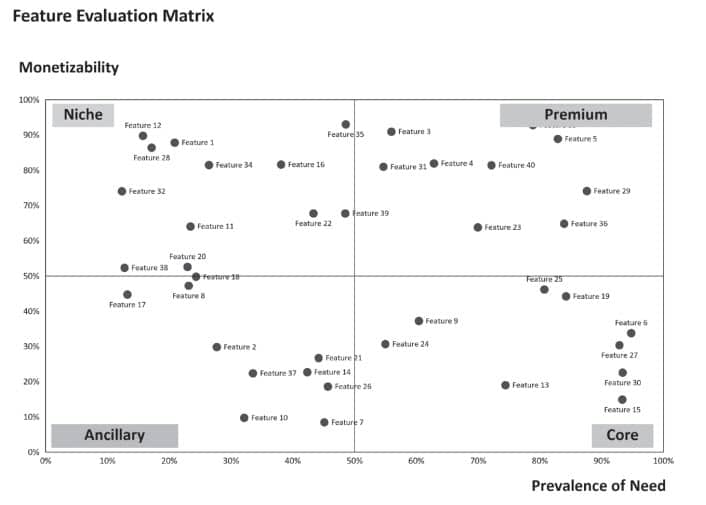

Martin: In the book, you present your Feature Evaluation Matrix as a framework for companies to evaluate their products against competitors’ offerings. Is this something companies should use on an ongoing basis as the market they sell into changes?

James: Companies will certainly get more value from it if they are able to revisit it on a regular basis. Competitors and products change but so do customers’ perceptions of value and what they expect from software. We’re seeing this with AI functionality being added to existing products. At the moment, many of those features will fall into the Niche quadrant as there are some customers who value them and are prepared to pay extra for them, but many will not. Such features are best monetized as add-ons. However, as time goes on and familiarity with AI features increases, they may move into the Premium quadrant, and can be included in premium tiers. Eventually, they could move into the Core quadrant as customers expect them as standard, at which point they should be included as standard (cost permitting!)

Martin: In the book you talk about hybrid pricing models, being a mixture of usage-based and fixed subscriptions. What types of products or companies would you say are best suited to a hybrid model?

James: I don’t think there’s any particular type of company best suited to a hybrid model. I think hybrid is either a good transitional point on the way to full usage-based pricing or a way of doing usage-based that allows you to lock-in recurring revenues. In this scenario, there needs to be a relationship between a usage metric and how your product creates value.

I see a lot of buzz around usage-based pricing and, speaking as someone who frequently builds such models, it isn’t really for everyone. It is not the case that in every product there is a measure of usage which dictates how much value is delivered to the customer. There are still a lot of cases where the number of seats is a pretty good measure of the amount of value they get.

If you are going down the usage road then you need a usage-based metric that grows over time. In some cases, products get better the more they are refined, and so, the amount of usage you need to achieve a certain outcome may reduce. If your pricing is tied to that metric, prices would decrease!

Many customers value predictability in their software costs. I’ve done studies which show a lot of enterprise customers would rather pay 15% more if they had the certainty that this is fixed and will not lead to unpleasant surprises. I don’t see that going away even with the advent of AI, so there will always be a place for pricing models that offer more price predictability

Martin: This speaks to my next question about psychology. People talk about B2B buyers being more rationale than B2C but at the end of the day it is still humans making decisions. How do you see this playing out in B2B?

James: I think psychology matters more than people think even in B2B sales. There is a tendency for us to assume we are more rationale than we actually are. While the B2B sales process is generally less of an emotional process than B2C, even a procurement professional, known for being very data-driven and rational, is probably not going to 100% rational all the time. It is still possible for them to be offended and react emotionally to what they see.

However, we need to differentiate between enterprises and SMBs (SMEs). Enterprise buyers are generally going to take longer over buying decisions, and be more logical, and so are less susceptible to pricing psychology. Small business owners are typically wearing multiple hats and don’t have the procurement systems and processes of larger companies. In this sense, they are more likely to act like consumers when making buying decisions, making quicker decisions based on gut feel, so psychological techniques work better.

A lot of vendors don’t take this into account when getting willingness-to-pay data. Choice based methods such as conjoint analysis work well with SMBs, as the process of choosing one option from 2-3 mirrors the gut-based buying process. Such models won’t work with large customers, as these buyers don’t buy in that way. They will want to do deep into functionality and make decisions where they see value being delivered. Getting to a price level by thinking about value delivered, ROI is more of a factor with enterprises than SMBs.

Martin: Moving onto AI and the pricing models being adopted here. In the book you acknowledge it is very early days but for the moment you are championing usage-tiered licence models. With the recent upheaval in the sector brought by the DeepSeek announcement of a much lower-cost model but performance similar to frontier models, has that made you rethink your approach?

James: I don’t think it changes the general strategy in the sense that usage-based tiers work because not all users are the same, and usage aligns to value. Power users of tools like ChatGPT get more value from it than infrequent ones. For example, I use ChatGPT frequently and if OpenAI told me that I’m using it so much they are going to raise the price to $40 a month then I might think that’s fair based on the value it gives me. I doubt more casual users would feel the same. Likewise, if the only option was for me to go from the $20 tier to the $200 pro tier, then I probably wouldn’t do it as that feels like too much for me.

At the moment, there are high costs to delivering these services, so usage-tiering has the added advantage of doing better at covering costs. If these costs come down, as DeepSeek has possibly demonstrated, then offer unlimited usage tiers becomes more viable from a cost perspective. But you’re still missing out on price differentiation opportunities.

Martin: DeepSeek is claiming they can process 250 tokens per second which has the potential to make real-time agentic AI a reality. What are your thoughts on this and what it might mean for pricing models in a world where autonomous agents are making decisions and running up costs in the background?

James: I think agentic AI changes everything because you are not consciously using it anymore, it’s just operating on its own. I think this will lead to a variety of different monetization models – user-based, usage-based, outcome-based etc. as value will be created in different ways by different types of agents. For example, a “personal assistant” agent may be best priced on a per user basis, as the value will likely be in replacing the administrative work of a human and so is about time saving. An agent that creates manufacturing efficiencies, on the other hand, might be best prices on the outcome – the cost savings through improved efficiencies.

Note that outcome-based pricing is aspirational, but practically difficult for vendors to adopt. One of the hurdles is that you must delay your revenue until your product has demonstrated how much value it has created. Many vendors are not willing to do that.

Martin: Thanks, James for such an interesting interview. Are there any other thoughts or messages coming out of your book that would like to mention?

James: Thanks, Martin. Yes, there is something I think important to get across.

There is a lot of excitement around GenAI and agentic AI, much of it justified. The software landscape is definitely changing and that is challenging many companies, vendors and buyers. However, while the technology may be changing the core pricing fundamentals and the ways we need to think about building a pricing strategy haven’t changed. In that sense, GenAI and agentic AI are subject to the same dynamics as everything else. It’s going to be based on a combination of how the products create value, what your customers want and need and what their expectations are. All these factors combined with what a vendor is trying to achieve are going to determine the optimal pricing strategy.

As the sector evolves, some of these factors will change and so the best solutions are going to change but the process of getting to the correct answer is exactly the same as it was 10 years ago.